Body dysmorphic disorder puts ugly in the brain of the beholder

By Ben Buchanan, Monash University

When people think of mental problems related to body image, often the first thing that comes to mind is the thin figure associated with anorexia. Body dysmorphic disorder is less well known, but has around five times the prevalence of anorexia (about 2% of the population), and a high level of psychological impairment.

It’s a mental disorder where the main symptom is excessive fear of looking ugly or disfigured. Central to the diagnosis is the fact that the person actually looks normal.

Neither vanity nor dissatisfaction alone

People with body dysmorphic disorder think there’s a particular feature of their face (such as nose, lips or ears) or another body part (such as arms, legs or buttocks) that’s unbearably ugly. Many seek unnecessary cosmetic surgery or skin treatments – but sadly only a few receive appropriate psychological support.

In general, people with the disorder are very shy and some choose to stay home out of fear of being judged or laughed at because of the way they look.

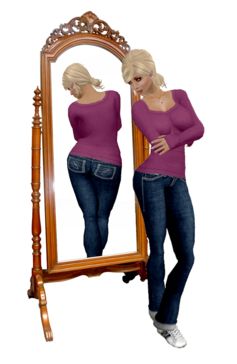

Many people with the disorder spend hours every day looking at themselves in the mirror. Others have unusual grooming habits to try and cover up their perceived flaw.

These people have significant difficulties with their social lives and experience high levels of anxiety and depression. Body dysmorphic disorder is clearly a serious problem and should never be dismissed as body dissatisfaction or vanity.

But distinguishing between these can be difficult, so the following questions are often used as a guide:

- do you think about a certain part of your body for more than two hours a day?

- does it upset you so much that it regularly stops you from doing things?

- has your worry about your body part affected your relationships with family or friends?

If someone answers yes to these questions, further professional evaluation is needed. A full assessment would entail a few sessions with a mental health clinician to talk about these worries and an assessment of grooming behaviours.

Brain research

My research using brain imaging has shown there are clear differences in the brains of people with body dysmorphic disorder that lead to changes in the way they process information. We found that people with the disorder had inefficient communication between different brain areas.

In particular, the connections between areas of the brain associated with detailed visual analysis and a holistic representation of an image were weak. This could explain the fixation on just one aspect of appearance.

There was also a weak connection between the the amygdala (the brain’s emotion centre) and the orbitofrontal cortex, the “rational” part of the brain that helps regulate and calm down emotional arousal.

Once they become emotionally distressed, it can be difficult for someone with body dysmorphic disorder to wind down because the “emotional” and “rational” parts of the brain simply aren’t communicating effectively.

People usually develop body dysmorphic disorder during their teenage years, which happens to be an important time for brain development. They also often report childhood teasing about their looks, which may act as a trigger that rewires the brain to focus attention on physical appearance.

Cosmetic procedures

Many people with body dysmorphic disorder seek cosmetic procedures such as nose jobs, breast implants or botox injections. The problem is that the vast majority (83% in some research) experience either no improvement or a worsening of symptoms after it. And most are dissatisfied with the procedure.

This differs from people without body dysmorphic disorder who are generally satisfied with cosmetic procedures and even report psychological benefits on follow-up.

Researchers estimate about 14% of people who receive cosmetic treatments have diagnosable body dysmorphic disorder, indicating that psychological screening practises are inadequate. Given the likelihood of causing psychological harm, it may be wise for cosmetic surgeons to assess all potential clients before operating.

Psychological treatment

It can be difficult to persuade someone with the disorder to accept psychological help given the belief in their physical defect is likely to be very strong. But once someone receives psychological therapy, symptoms are likely to reduce.

The first-line of treatment is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), focusing on exposure and response prevention with the option of antidepressant medication. This helps patients modify unhelpful daily rituals and safety behaviours, such as mirror checking or camouflaging the perceived defect with make-up.

Body dysmorphic disorder is under-diagnosed because those with it persistently deny they have a psychological problem, preferring to opt for physical treatments instead. Evidence suggests that symptoms are underpinned by differences in the way the brain processes information and that psychological therapy can help people overcome the preoccupation their with appearance.

Ben Buchanan is involved in research and treatment of body dysmorphic disorder. The brain research referenced in this article was funded by a Monash Strategic Grant. Ben conducts research at MAPrc (Monash Alfred Psychiatry Research Centre), School of Psychology and Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University and The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.